- Home

Page 19

Page 19

Victoria Line, Central Line

Victoria Line, Central Line Maeve's Times

Maeve's Times Evening Class

Evening Class Minding Frankie

Minding Frankie London Transports

London Transports The Lilac Bus

The Lilac Bus A Few of the Girls: Stories

A Few of the Girls: Stories A Week in Summer: A Short Story

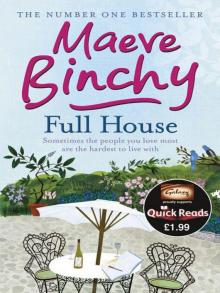

A Week in Summer: A Short Story Full House

Full House Scarlet Feather

Scarlet Feather Dear Maeve

Dear Maeve Light a Penny Candle

Light a Penny Candle Tara Road

Tara Road Circle of Friends

Circle of Friends Maeve Binchy's Treasury

Maeve Binchy's Treasury The Return Journey

The Return Journey Heart and Soul

Heart and Soul Aches & Pains

Aches & Pains The Builders

The Builders Whitethorn Woods

Whitethorn Woods Echoes

Echoes Nights of Rain and Stars

Nights of Rain and Stars Silver Wedding

Silver Wedding Dublin 4

Dublin 4 A Few of the Girls

A Few of the Girls Sister Caravaggio

Sister Caravaggio Lilac Bus

Lilac Bus Binchy ( 2000 ) Scarlet Feather

Binchy ( 2000 ) Scarlet Feather